The difficulty with meditation and mindfulness practice

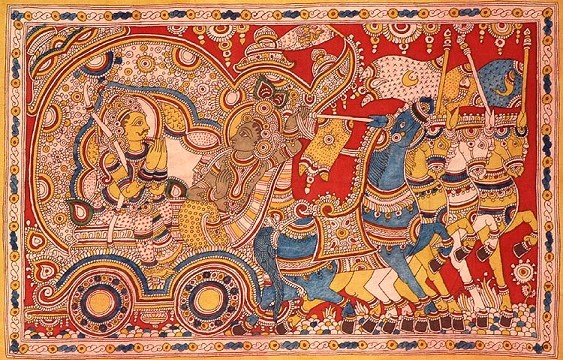

Pic Courtesy: Kalamkari artists featured in exoticindia.com

Lately, I have been reflecting a great deal about meditation. Over the past 15 years, I have had a relatively regular but constantly shifting meditation practice, but in the past few weeks, I have had a slew of extremely frustrating and challenging moments where I feel like throwing up my hands to the sky. I have thought about giving up on meditation altogether because my mind is constantly unfocused and wavering no matter how often I sit to practice, and my emotions have come spilling out in dramatic episodes of tearing up and even outright bawling. I have been asking myself, even with a regular and committed meditation practice, am I ever going to get the hang of this? If not, then what is the point of practicing at all?

I am quite sure that I have already accumulated the 10,000 hours of practice that progressive thinker and writer Malcolm Gladwell says is necessary to master a particular skill or craft or interest (see his popular book The Outliers”) But, I don’t think Mr. Gladwell had meditation in mind when he was discussing this 10,000 hours rule, because meditation is a completely different realm of skill, art and science. Even after 10,000 hours, I have not mastered meditation at all; instead, I keep digging deeper into my own inadequacy, lack of focus, unstable mind, and rollicking emotions. I sometimes feel that the more I meditate, the more troublesome my mind becomes.

For those of you out there who have tried meditation and/or have a regular practice, it’s wonderful that you have explored this part of yourself. Meditation has amazing benefits that have now been thoroughly researched and scientifically proven by all those who only believe in hard, tangible evidence. I would never say that I would be better off without meditation in my life, but at times I am unaware as to how it is really affecting my mind, including my thinking, decision-making, and emotional processing. Basically, I still feel like a mess. I think my expectations around who I should be 15 years after a regular meditation practice may be unrealistic taking into consideration the fact that it is an ancient practice that even challenged Buddha himself. Buddha spent more than 6 years doing little else but meditating and reflecting on relieving suffering before he attained his enlightenment, and this was after already spending time following yogic and ascetic practices and other strategies to escape suffering.

So, why continue to meditate when the odds seem stacked against me that I will ever master this skill at all? Often, when I am trying to search for answers to my unanswerable questions, I pick up one of my go-to resources, the Bhagavad Gita (my version was translated by Eknath Easwaran”). The Gita often has a message for me no matter what state of mind I am in. There is always a key word, wise sentence, poetic paragraph, or enlightening phrase that helps me to reconnect to why I pursue my spiritual practice. So, as I have been thinking about meditation and its meaning in my life, I have turned to Chapter 6 of the Gita. In this chapter, Krishna describes the practical steps that one must follow in order to meditate.

First, Krishna describes the qualities of those who have conquered their minds (i.e. egos) and discovered the Self within. He mentions how these individuals have conquered the senses (i.e. cravings, desires, and aversions) and that they treat all living beings the same in an impartial manner. Krishna goes on to describe that one who aspires to the state of yoga should meditate by practicing one-pointedness without attachment or expectations. He describes all the practical steps to set up for meditation, and then how to actually meditate. He also describes how one must conduct their lifestyle in order to succeed in meditation (e.g. proper eating, sleeping, work, leisure habits).

What stood out for me in my most recent reading was Krishna’s description of the quality of the mind once meditation is mastered: “unwavering like the flame of a lamp in a windless place”. This is a beautiful image that connotes the steadiness of a meditative mind that does not get attached to anything, and that is completely centered and calm. Krishna is saying that when a person meditates consistently with patience and commitment, it is only a matter of time for them to discover who they really are.

Arjuna, the warrior and spiritual disciple with whom Krishna is conversing in the Gita, points out his strong doubt that the restless mind can ever find lasting peace. Krishna agrees that the mind is difficult to control but gives Arjuna faith that it can be conquered through self-control and effort. Arjuna is preoccupied with his concern that a person who fails at both meditation as well as the achievement of a materially rich life would lose the support of both worlds like a “cloud scattered in the sky”. Krishna reassures Arjuna that a person who tries to find the Self through meditation could never be destroyed or come to a bad end. He tells Arjuna that they will be reborn into a family where meditation is practiced to reawaken the wisdom from their previous lives. He is saying that even if one is not able to become enlightened through meditation in this life, they will have the opportunity to do so in a future life. But, that seems like a long time to wait!

Arjuna’s doubts in this chapter really resonate with me, particularly the doubt about the restless mind ever being able to attain lasting peace, and the doubt about whether or not one with faith but without self-control (and who thus then wanders off the spiritual path) would ultimately end up a lost soul. I am always questioning the capacity of the mind to ever sit still. But, that being said, I have had glimpses of complete stillness in my life, so I know it is possible. It is sustaining that still, calm flame that is the challenge, but I know this is the constant practice for the individual who has the desire to meditate as a part of their spiritual journey.

After reading Chapter 6, I was reminded of the reason why I meditate at all, and why even some meditation is better than no meditation. Truly, my meditation is a practice of love and devotion. Most likely, I will never become enlightened like the Buddha in this lifetime or even in future lifetimes, but I know I have the capacity to live my life more authentically with devotion, love, and reverence for myself and for others. Being able to meditate in a perfectly peaceful state is not what is required. What is required for each individual who cares to explore a meditation practice is the determination to deal with one’s suffering, to find one’s true Self, and to follow along on the spiritual path that we are meant to travel on.

If I can be a “flame in a windless place” for even a single moment in my day, I have experienced something magical.